| by Maurizio Berlincioni

Dorothea Lange was born in Hoboken, New Jersey, of a family of German immigrants. She studied photography at Columbia University under the guidance of Clarence H. White and in 1912, when a mere nineteen years old, opened a portrait studio in San Francisco.

Her adolescent and teenage work was, for the most part, characterised by a quest for synthesis and clarity and a taste recognised for its stylization and psychological enquiry, though remaining very much a part of the contemplative and aesthetic context of the fashionable portrait photographers of that period.

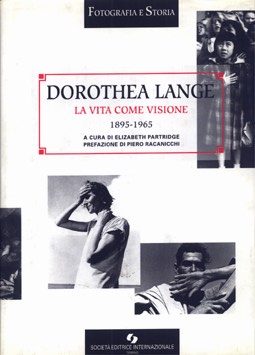

Dorothea Lange brutally detached herself from this way of 'seeing' at the beginning of the Thirties when she began to produce decisively more radical pictures (like the very famous White Angel Breadline in 1932).  | An Italian book

with the phothgraphs of

Dorothea Lange | She manifested thus her enormous illustrative ability to get to the heart of man and the environment in which he lived and worked, "in search of the truth in everything and at any cost, as she herself said. In her mature artistic years this became the foundation of her undertakings and her poetics.

In the words of Piero Racanicchi: "...in her photos, devoid of any external smugness or any formal and conventional adjective, Dorothea Lange documents without being bound to documentation; she describes without shackling herself to the newsreel or description for description's sake."

Her participation in the great FSA project from 1935 carried her in pursuit of the migratory flood towards California, where she captured the expressions of men, women and children that reveal better than any written commentary the dismay and disorientation of these human beings left to themselves.

In his article in the Popular Italian Photography, Racanicchi defines the portrait of the migrant Mother as "without question the most poignant of Lange's photographs, certainly one of the best we have seen since the advent of photography".

A connoisseur of the German New Objective movement in painting, of its themes and visual cuttings, she was forever very attentive to all the phases of her own work, supplementing it with notes, interviews, impressions and suggestions about the final cut of the picture and its layout, a layout made for small blocks that closely recalls some of the famous sequences from the films of Ejzenstein.

In the opinion of A.C. Quintavalle "...Dorothea Lange lays out her pieces following a definite tradition. She rejects a "continuous" time outside of her photographs which thus would or would want to present themselves as "clippings"; every photograph for her is a synthesis."

As happened to many of her contemporary American writers - Faulkner, Hemmingway or Dos Passos to name but a few of the most famous - she came across in her work a narrative fabric whose flow is continually broken by private stories, which are then focused on in a dramatic fashion, stretched out to form a tale where the theme makes itself felt through these fragments while the unifying argument almost disappears or becomes the background to a sequence reminiscent of a film.

It's no coincidence that many of her pictures look like photos from the set of the film The Grapes of Wrath (adapted from Steinbeck's famous novel): as a matter of fact it was first the author and then the director John Ford that admitted to having been inspired in their work by the photographs of Dorothea Lange.

From the point of view of thematic choices, Dorothea Lange is the least specialized of the FSA photographers. Any topic might find itself playing a part in her narrative: her object is to portray characters in an anthropological sense, as meaningful figures, taking account of their totality and creating thus an epic vision that imparts to us indications of a system and a mythology ( that of the journey, of exodus).

(©1997 M.Berlincioni)

Bibliography |